By matthew hesselgrave adhd coach, bipolar coach

The Neurochemistry of ADHD: Unraveling the Unique Brain Differences

The human brain is an intricate, multifaceted organ responsible for our thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. Neurochemistry, the study of how neurotransmitters and other molecules in the brain influence our cognitive and emotional processes, plays a vital role in understanding various neurodivergent conditions, including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). In this blog post, we will explore the fascinating world of neurochemistry and the unique differences in the ADHD brain.

Neurotransmitters and ADHD: A Complex Relationship: Neurochemistry hinges on neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that facilitate communication between neurons. In the context of ADHD, several neurotransmitters play a crucial role. Let’s delve into the most prominent ones:

1. Dopamine: The Key Player: Dopamine is often referred to as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter because of its role in reward and pleasure systems. In the ADHD brain, dopamine is of particular significance. Research suggests that individuals with ADHD have altered dopamine levels and receptor activity. Here’s how dopamine is involved:

a. Hypofrontality: Individuals with ADHD often exhibit lower levels of activity in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region crucial for executive functions such as impulse control, attention, and working memory. Dopamine deficits in this region contribute to these symptoms.

b. Reward System Dysregulation: The brain’s reward system relies heavily on dopamine. ADHD individuals might seek instant gratification and reward, leading to impulsive behaviors and a reduced ability to delay rewards.

c. Medication and Dopamine: Many medications used to treat ADHD are designed to increase dopamine levels or improve its utilization in the brain. These medications can help enhance focus and reduce impulsivity.

2. Norepinephrine: The Alertness Neurotransmitter: Norepinephrine, another key neurotransmitter, is essential for maintaining wakefulness and attention. In individuals with ADHD, norepinephrine levels may be imbalanced. Here’s how it influences the condition:

a. Attention and Arousal: Norepinephrine regulates attention and arousal, so itsdysregulation can result in difficulties in maintaining focus and alertness.

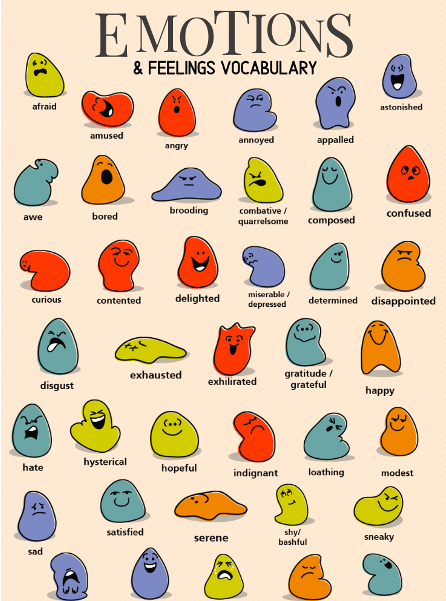

3. Serotonin: Mood and Emotions: While serotonin is often associated with mood regulation and emotional well-being, its role in ADHD is not as pronounced as that of dopamine and norepinephrine. Nonetheless, it can influence emotional regulation and impulse control in individuals with ADHD.

ADHD Brain Structure and Neurochemistry: The neurochemistry of the ADHD brain is closely intertwined with its structural differences. Neuroimaging studies have revealed distinct patterns in brain structure and connectivity among individuals with ADHD. Some of the noteworthy findings include:

1. Smaller Prefrontal Cortex: The prefrontal cortex, a region associated with executive functions, is often smaller in individuals with ADHD. This structural difference contributes to challenges in impulse control and attention.

2. Altered Connectivity: Connectivity between various brain regions is also different in ADHD brains. Researchers have noted weaker connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions responsible for attention, which can affect focus and self- regulation.

3. Corpus Callosum Differences: The corpus callosum, a structure connecting the brain’s hemispheres, exhibits differences in individuals with ADHD. These differences can impact the coordination and communication between the brain’s two halves.

Genetics and Neurochemistry in ADHD: ADHD has a strong genetic component, and genetics can significantly influence neurochemistry in the ADHD brain. Several genes associated with dopamine regulation have been linked to the disorder. While not everyone with these genetic variations develops ADHD, they can contribute to an increased risk.

Environmental Factors and Neurochemistry: Beyond genetics, environmental factors can also impact the neurochemistry of the ADHD brain. Exposure to toxins, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and early life stress can all influence the development and functioning of neurotransmitter systems.

The Impact of Medication: Medications used to treat ADHD, such as stimulants like methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamines (Adderall), primarily target dopamine and norepinephrine systems. These medications help improve focus, impulse control, and hyperactivity by increasing the availability of these neurotransmitters in the brain.

Non-Medication Interventions: While medication can be highly effective, it’s not the only option for managing ADHD. Behavioral interventions, therapy, and lifestyle changes can also have a significant impact on the neurochemistry and overall well- being of individuals with ADHD.

Diet and Nutrition: Certain dietary changes, such as reducing sugar and processed foods, and incorporating more omega-3 fatty acids and protein, can positively influence neurotransmitter levels and, consequently, symptoms of ADHD.

Physical Activity: Regular physical activity has been shown to increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain, helping to improve attention and mood.

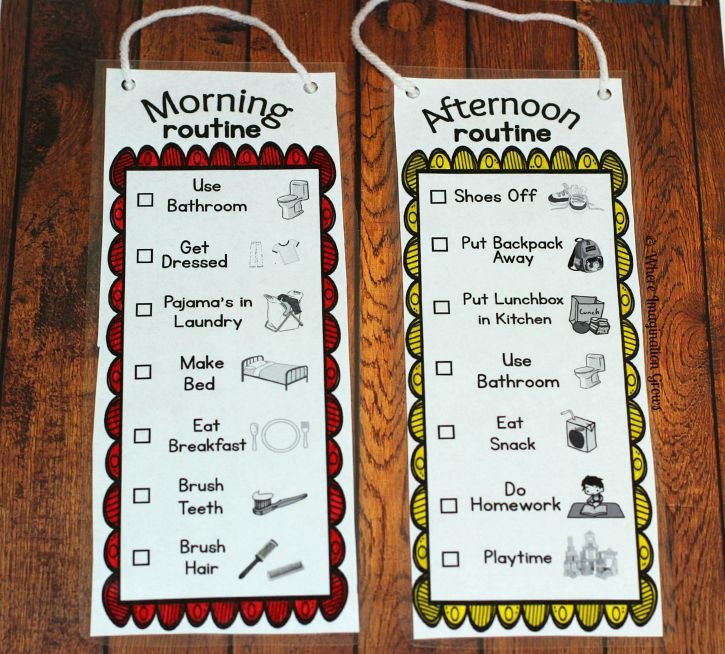

Behavioral Therapy: Behavioral interventions including coaching can teach individuals with ADHD practical strategies for managing their symptoms, enhancing executive function, and improving their overall quality of life.

Understanding the neurochemistry of the ADHD brain is a crucial step in destigmatizing the condition and improving the lives of those affected by it. While ADHD presents unique challenges, it’s also associated with strengths, creativity, and innovation. By recognizing the intricate interplay of neurotransmitters, genetics, and environmental factors in the ADHD brain, we can better support individuals with ADHD, reduce stigma, and develop more effective interventions to help

If you resonated with this information and want to talk further about ADHD and the impacts you are feeling, reach out today.